Knowing More About Christmas (Part 1): The ‘Pagan’ Words We Use Every Day

A look at the etymology of "Christmas," the calendar, and why origin doesn't always equal meaning.

By: Eusebio Tanicala

Every December, a familiar discussion surfaces among sincere believers regarding the vocabulary we use during the holidays. For this first installment of our series on Christmas, I want to dwell on two specific items: the terminologies we use without question, and the specific etymology of the word "Christmas."

The Argument Against "Christmas"

A common objection raised by many Christians is that the word "Christmas" is a compound of Christ + Mass, clearly pointing to a Catholic origin. The argument follows that by using the term, we are inadvertently perpetuating the errors of that ecclesiastical system or validating a "mass" for Christ.

However, this objection often lacks merit when we examine it through the lens of consistency. If we refuse to use the word "Christmas" solely because of its origin, we find ourselves in a difficult position regarding the rest of our vocabulary. We currently use—without question—many other words of similarly objectionable origin which, like "Christmas," have undergone modification and no longer convey their original heathen sense.

Examining the "Pagan" Days of the Week

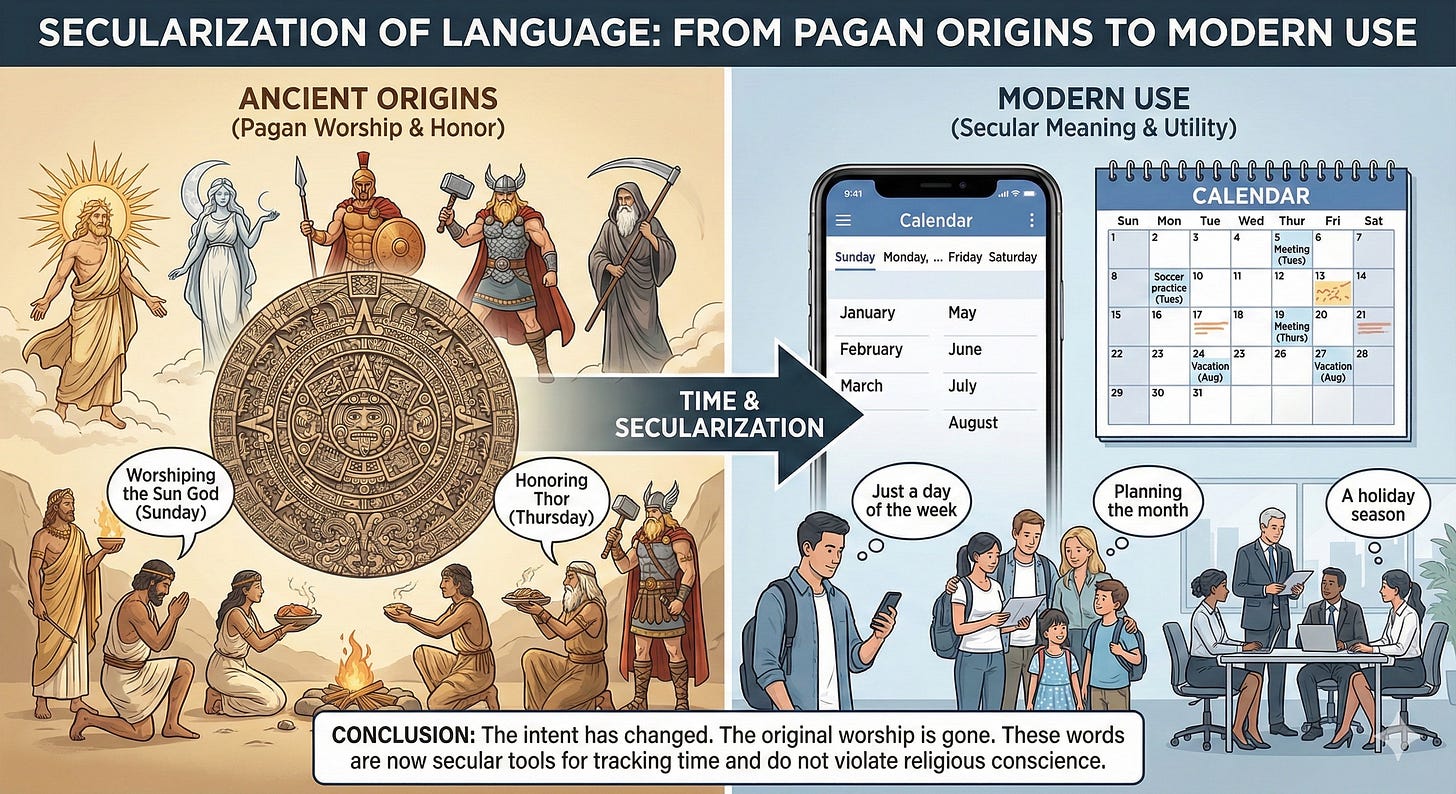

Consider the origins of our calendar. The pagans who invented the names of our days worshipped false deities. Naming the days after these gods was a specific act of worship and honor. Yet, many of us are unaware of the background and etymology of the days we mention constantly.

Consider the origins of our week:

Sunday: Old English for "Day of the Sun."

Monday: Old English for "Day of the Moon." (In Spanish, luna is moon, from which Lunes in our Philippine dialects is derived).

Tuesday: The Old English form was Tiwesday or "Day of Tiw," an ancient Teutonic deity. However, Latin and Spanish changed it to Martes (used in our dialects) in honor of Mars, the Greek and Roman god of war.

Wednesday: "Woden’s Day," honoring Woden, a chief idol of mythology.

Thursday: Old English Thunor, the short form is Thor. This was changed into Jueves in our Philippine dialects by the Spaniards in honor of Jove—another name for Jupiter of the Romans (Zeus of the Greeks).

Friday: Derived from the Norse goddess Frigg, the wife of the chief god Odin.

Saturday: Derived from Saturn, the second-largest planet and, in Roman mythology, the god of agriculture.

We do not have negative reactions to these pagan weekday terms because the heathen religious shade of meaning has disappeared.

To us, the days of the week bear no resemblance to their earlier usage; we use them in harmony with their meaning to us, not their meaning to ancient pagans.

I have a good friend whose family name is Saturno, evidently derived from the pagan deity Saturn. Shall we mark him unworthy as a brother because he bears that name? Shall we urge him to legally change his name to Cristiano? Of course not.

The Pagan Names of Our Months

It is not just the days of the week; the names of the months were also invented by ancient pagans to honor their worldview:

January: Named for Janus, the Latin god of beginnings or entrances.

February: From Februa, a Roman deity whose festival is celebrated on the 15th of February.

March: Derived from Mars, the Roman god of war.

May: From Maia, the goddess of growth.

July: Named after Julius Caesar of Rome.

August: Derived from the Roman Emperor Augustus Caesar (27 B.C.- 14 A.D.).

Furthermore, the very system we use to track time, the Gregorian Calendar, was issued by the Roman Catholic Pope Gregory XIII in A.D. 1582. It replaced the Julian Calendar of Gaius Julius Caesar, the strongman of Rome (100-44 B.C.).

Conclusion

Although the names of our days and months are undeniably derived from pagan mythologies and figures, the worship and honor for those ancient deities no longer reside in those words. The intent has changed.

Because these words have been secularized, they do not offend us and should not affect our religious beliefs. In the same way, "Christmas" to most people today is not a "mass for Christ," but a holiday—a season of joy, gladness, and warmth where friends and family gather. These terms are now secular in nature and need not intrude into our religious sensibilities.